Are electronics free, fully 3D printed robots achievable?

This summer, I briefly joined the Bioinspired Robotics and Design lab at UC San Diego to undertake a summer research project on 3D printed soft robots. Unlike their rigid, electronically powered counterparts, these soft robots employed low shore hardness thermoplastic elastomers (TPEs) and pneumatic circuits to function.

This project employed the MAMMAMIA system to print exceptionally soft materials by using pellet feedstock instead of traditional filament. While using pellet printing to fabricate delicate, airtight components was a challenge that required extensive process tuning and design iteration, it allowed us to create unprecedented results.

Process Optimization for Extremely Soft Pellet Printing

Printing airtight components is a difficult challenge in FDM due to the residual air gaps that are left behind between lines of material and seams. Meanwhile, printing with soft materials such as SEBS (Styrene Ethylene Butylene Styrene, Shore A 47 hardness), great care must be taken to prevent the part from deforming under its own weight and the pressure of the nozzle.

We conducted a preliminary series of experiments to find a set of print parameters that allowed us to print small details, overhangs, and bridges while still producing leak-free walls. The lessons learned in this stage will support future pellet printing projects in different fields.

Kinked Channel Control Valve

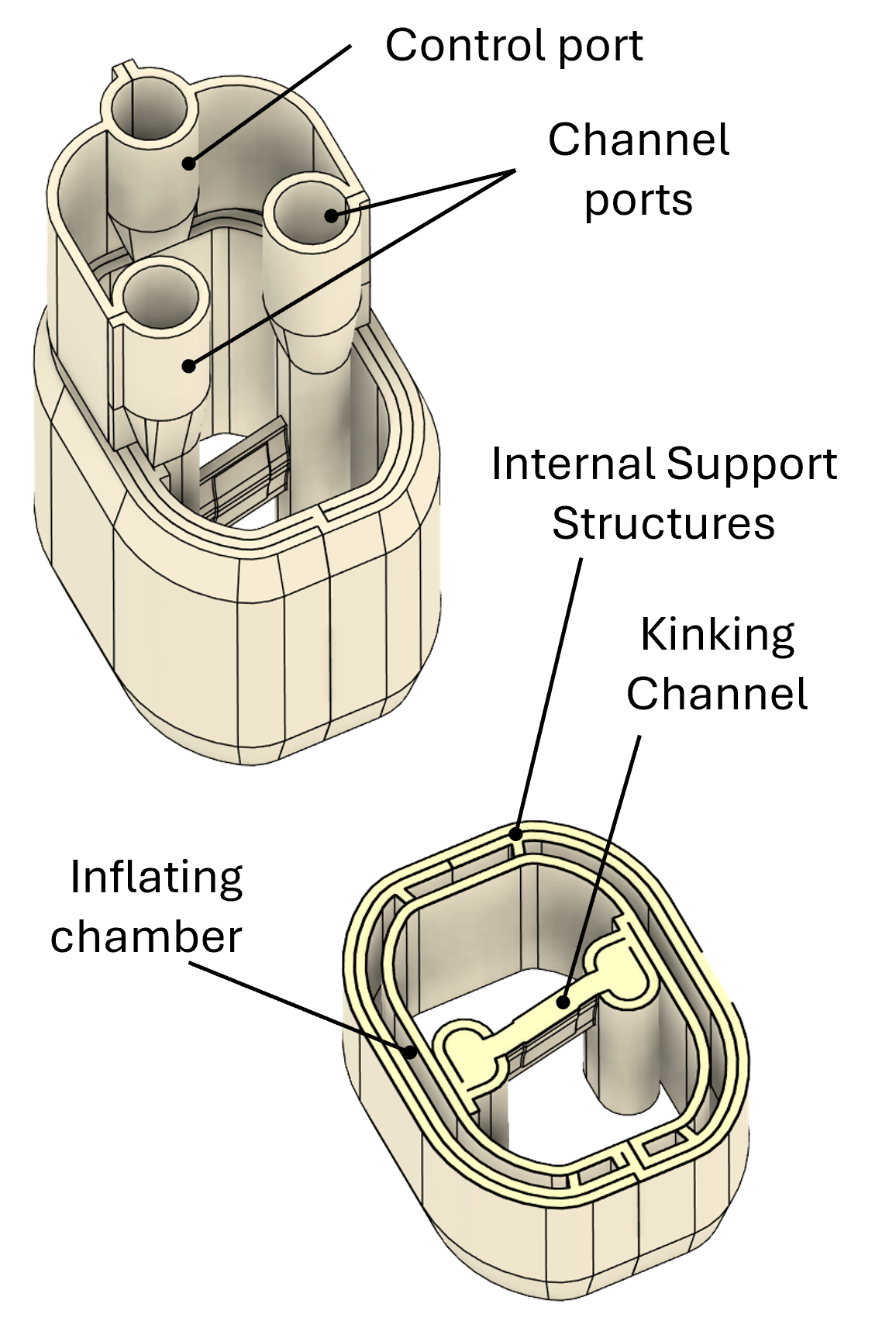

Pneumatic control valves are a critical part of soft robotic logic circuits. The valves designed for this project were monolithically printed - requiring no support removal or assembly. To achieve the precision required to print these airtight pneumatic components, a novel CAD design approach was used to explicitly design the exact toolpath of each layer instead of relying on slicer algorithms. When pressurized, this valve kinks an internal air channel, cutting off through flow.

Duckbill Inspired Check Valve

Prior to this project, there was no precedent of printing normally closed valves. This is because it is difficult to print a valve mechanism in an initially closed state without causing it to fused shut.

To circumvent this, we conceptualized a switchable check valve similar to commercial duckbill valves. This mechanism featured an internal membrane which would self-seal when pressurized, restricting flow. However, the membrane could be buckled open by applying force to the sides of the part. This allowed us to integrate touch sensing and interactive buttons directly into our soft robotic designs.

Low-Exhaust Gripper with Integrated Sensing and Actuation

The development of a new normally closed valve allowed us to print a soft robotic gripper with exceptionally low air usage. Prior versions of this design continuously exhausted approximately 7000 standard cubic centimeters per minute in order to function. Conversely, our design only required air to pressurize the actuators, and had zero standby exhaust when holding an object.

This project pushed the boundaries of what we can 3D print, while developing novel design for additive manufacturing (DFAM) methods that give us more control over not just what we print, but exactly how it is printed.